The day before this week’s workshop I had spent half an hour online, talking to Mohegan theatre maker Madeline Sayet. I saw Madeline’s show at the London Origins festival and loved it. Not only did she talk about her love both for Shakespeare and her Mohegan heritage, she also spoke of Mahomet – the Mohegan tribal leader whose burial in Southwark is marked in the Cathedral grounds with a stone mound carved by swirling ridges.

Madeline had asked me ‘what is the question that underpins the project’, so I started this week’s session by posing this to the group. (Dotty, David, David, Deborah, Harriet, Jane, Yvonne, Keitha).

The immediate response was ‘Why the Mayflower’ – why among all the arrivals, is it the Mayflower that we remember. Then perhaps, ‘why did they continue?’ and ‘why is it relevant to us today?’ I have been wondering whether we should re-title the project ‘Charting the Mayflower English colonisation of America 1600-1630’.

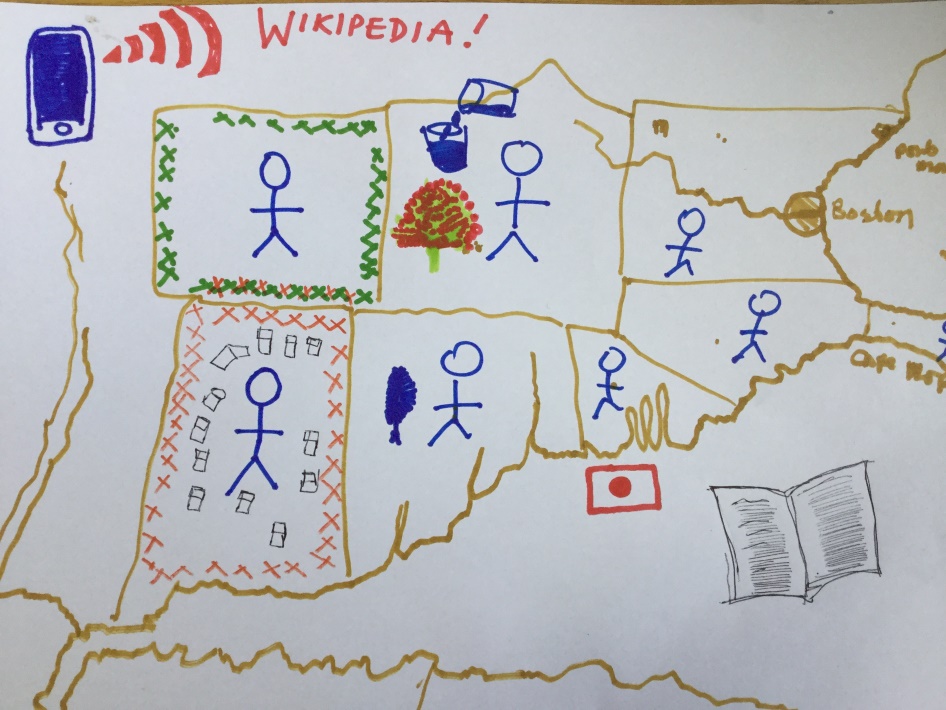

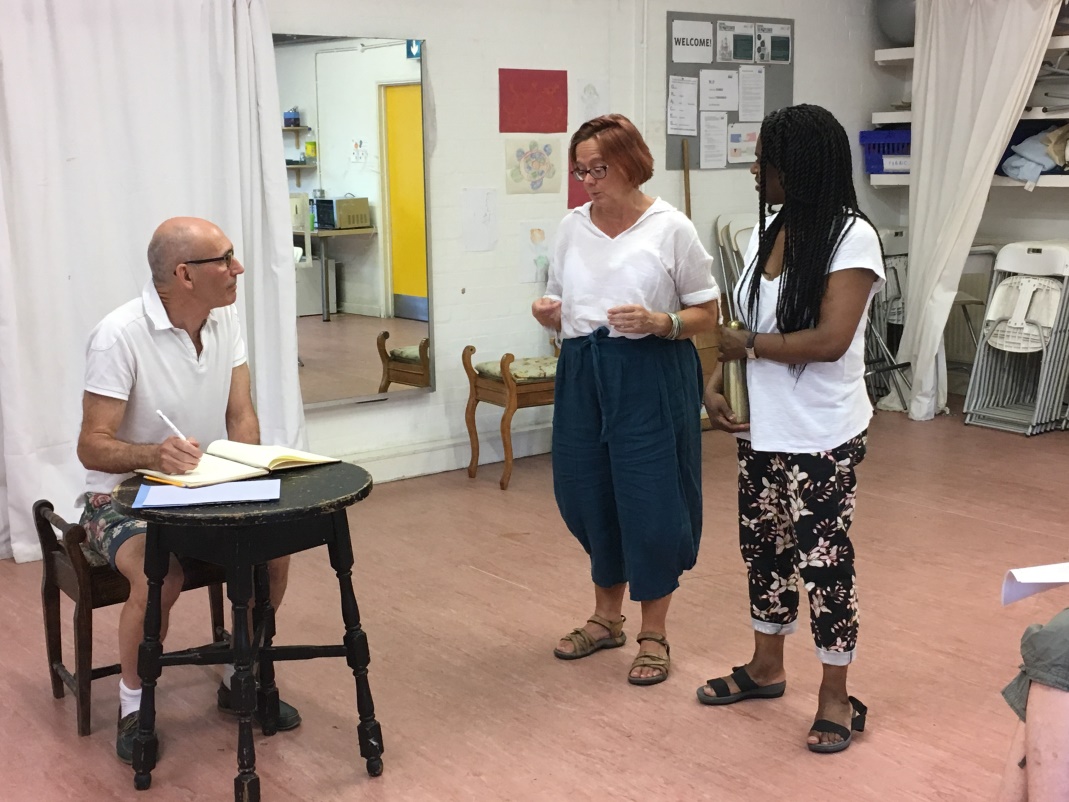

The question for this particular session was ‘how events are passed on’. The first event we ‘passed on’ was last week’s workshop. We were lucky to have 3 people who hadn’t been there so we conducted an experiment – 2 of those who had been there were to pass on that event through a drawing, 2 were to write a journal entry and 2 were to pass it on through spoken word. The three non-attenders took it in turns to take on the information through each of the 3 mediums.

We then talked about how different parts of mind and emotions are engaged by different media, where there were contradictions or omissions and what was most open to interpretation.

The thinking behind this exercise was to consider the difference between the way the English chronicled the events of 1620-21 – mainly through journals – and the very different Wampanoag chronicling – which is done through oral history re-told both in families and by the medicine woman of the tribe.

We then reciprocated – Deborah, Lucy and Keith (last week’s non-attenders) had been recalling an ‘encounter in a new place’ and they now passed this event on – one through a picture, another through writing the third through a telling. Each of the three original groups were gifted one of these – the picture story, or the written story, or the told story – and then they in turn were asked to tell that story back to the wider group. We wondered how this re-iteration of history might change the event.

The original authors seemed to enjoy their tales being given another voice – even the interpretation of Queen Deborah walking on water (which was actually a loosely drawn escalator) got the approval of the author. It felt like the passing on of these events was a creative and social action as well as a more factual recording.

The last part of the evening focussed on Mourt’s Relation. This was the English way of recording events and was originally printed in 1622 under the title A Relation or Journal of the English Plantation settled at Plymouth. A very quickly shared first hand account of the settling published in London.

We worked from the journal entries from the first week in Cape Cod which described a 3 day expedition along the beach and into the woods, including first glimpse of the Wampanoag. Each of the three groups took 1 of the 3 days and read and discussed the events. We then set up a scenario which saw them arriving back from the trip and having to explain the events to a diarist. So two people re-told and another person – who hadn’t been on the trip – wrote what eventually would become Mourt’s Relation.

What we saw was very human and quite funny. Events were sketched in and disputed. Some things were emphasised for quite subjective reasons (Harriet couldn’t stop going on about the craftsmanship that had gone into the rope trap that had ensnared William Bradford). Other things were glossed over in case anyone might disapprove – “we put everything back in the grave just as we found it – I don’t think anyone will notice”. Other events were just told too quickly for the diarist to write.

Yes, Winslow and Bradford and the others probably wrote more thoughtfully and they had the opportunity to interrogate the tellers. But they were human. The writers of what we might take as fact were opinionated, flawed and aware of their audience. I would love to know what they left out and, of course, how the Wampanoag recounted what they saw.

Jonathan Petherbridge

5.7.19